The Traveling Artist in the Italian Renaissance by David Young Kim

Author:David Young Kim

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2014-08-24T16:00:00+00:00

LORENZO LOTTO: ABOLITIO MEMORIAE

Sebastiano is tarred and feathered for his mobility and ensuing masquerade of disegno. By contrast, an itinerant artist such as Lorenzo Lotto largely meets indifference, though with a telling moment of criticism flashing through. The different paths these artists’ journeys took may partly account for this discrepancy: Sebastiano was active in the recognizably pivotal artistic center of Rome, while Lotto pursued a “provincial” career largely in the Marches and Bergamo. Lotto’s work in locations removed from the triumvirate of Venice-Florence-Rome thus did not become hefty weapons or targets in the regional debates which evaluated the merits and shortcomings of central versus northern Italian styles. Instead, the Dialogo brushes Lotto off, ostracizing him from that preeminently Venetian stylistic domain—coloring and brushwork. This dismissive stance contrasts with that of Vasari, who presumes Lotto’s excellence in coloring, given his Venetian origins. These differing attitudes toward Lotto betray tacit assumptions concerning the bond between regional identity and regional style and, moreover, how mobility can put stress on that bond.53

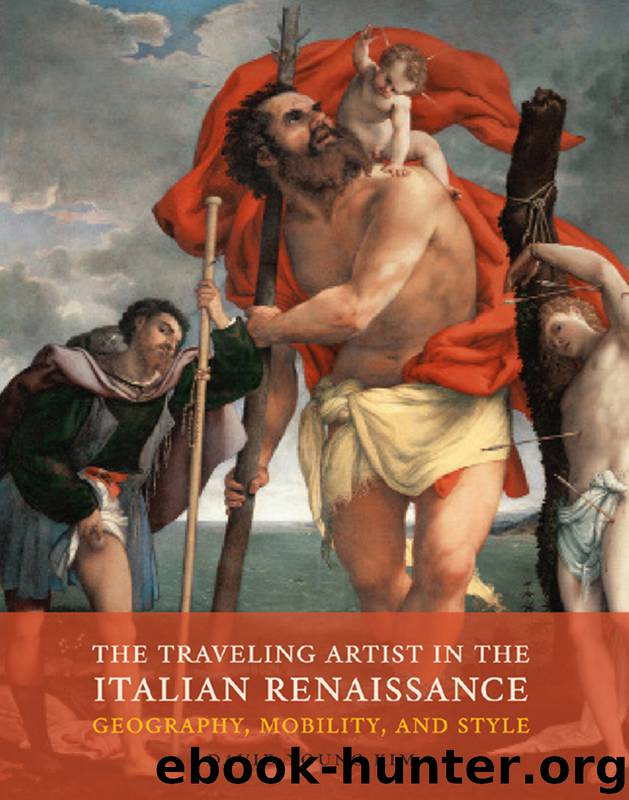

The sole reference to Lotto in the Dialogo appears after an extended discussion of coloring. “When the painter produces a good imitation of the tones and softness of flesh,” Aretino observes, “he makes his painting seem alive.” Later in this passage, he reiterates the necessity of keeping the eye fixed on tones, “primarily those of the flesh areas, and on softness.” To emphasize these qualities, Aretino evokes stone and minerals as counterexamples. Some errant painters render flesh “such that they seem made of porphyry, both in color and hardness.” Other misguided artists portray lips that appear to be of coral, with faces that look like masks. Interjecting, Fabrini offers Lotto’s altarpiece St. Nicholas of Bari in Glory (c. 1529) as a specific negative example: “It seems to me that a notable enough instance of these pernicious tones is to be seen in a painting of Lorenzo Lotto’s, which is here in Venice in the Church of the Carmine” (see fig. 1.9).54

To take Fabrini’s comment at face value is a sensitive matter; after all, the Dialogo’s ultimate goal was to praise Titian to the detriment of his foreign rivals and compatriots. Even so, stylistic features, such as a rather outmoded polished brushwork and a hieratic compositional format derived from northern models, may have motivated the criticism against Lotto’s altarpiece. Although painted on canvas, Lotto’s work reveals his training as a painter deeply conversant with fifteenth-century modes of coloring on panel. Much like his predecessors such as Giovanni Bellini and Cima da Conegliano, Lotto executes the detailed texture of St. Nicholas’s damasks, cloth of gold, and jeweled pendants in discrete passages of carefully applied paint layers and white highlights. Of course, the striking combination of the colors—violets, greens, and oranges—is more indicative of Lotto’s own idiosyncrasies rather than any indebtedness to Venetian pictorial tradition. Even so, Lotto’s controlled brushwork differs markedly from his contemporaries’, notably Titian. Already in such large-scale compositions as that of the Ca’ Pesaro Altarpiece (1519-26) and earlier in the Assumption of

Download

The Traveling Artist in the Italian Renaissance by David Young Kim.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18605)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5452)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3659)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3526)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3511)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3431)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3340)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3287)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3155)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2903)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2900)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2867)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2705)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2703)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2646)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2622)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2569)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2562)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2494)